Here's an interesting read from the National Post.

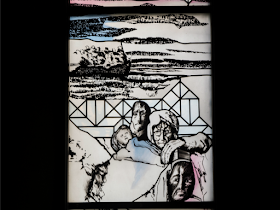

The stained glass refugee window at St. Andrew’s Church on Jarvis Street faces south toward Lake Ontario. It is not displayed prominently. Walk by it, and you are liable to miss it.

But stop and look up, and what you will see is a Gothic church window unlike any other. There are no Jesus, Joseph or Mary or crosses or saints or other symbols of faith, but a grim, almost colourless scene, rendered in greys and blacks, depicting a boat full of people with haunted expressions — refugees from more than 70 years ago.

“That church window matters today,” says Eneri Taul. “We are facing a refugee crisis with the Syrians. But it is a crisis we faced in 1944, as Estonians. It was the last time to escape from that country.”

Leaky fishing trawlers, loaded with refugees, and tossed about on stormy Baltic seas while being preyed on by dive bombing Russian fighter planes and lurking submarines, are central to the exodus stories from the Baltic States.

Estonia was occupied three times during the Second World War — initially by the Soviets, then by the Germans and then again by Soviet Russia, a state that no longer exists but remains resoundingly unpopular among Estonians. (The three Baltic states, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, hold ceremonies on June 14 each year, marking the date in 1941 when the Soviets deported tens of thousands of their citizens to Siberia where most perished).

After temporarily losing their hold on Estonia to Germany the Russian army rolled back in, in 1944, pushing tens of thousands of refugees ahead of them.

Their only escape was by boat.

“I remember everything about it,” says Ivar Nippak, who was eight. “I remember bullets clanging off the boat’s deck. But what frightened me most wasn’t the bombs, but the white flares that the Soviet fighter planes dropped, casting everything in light.”

We are drinking coffee and munching on kringel — imagine a succulent, cinnamon-raisin Christmas bread, and that is kringel — while talking about the past and an old church window’s connection to the present at Estonian House in the city’s east end.

There is a gift shop in the lobby full of Estonian books and assorted doodads. The Estonian credit union is upstairs. So, too, is the Estonian consulate that when times were different back in Estonia, and the tiny Baltic nation was trapped behind the Iron Curtain, subject to the brutal whims of the Soviet leaders in Moscow, was the consulate-in-exile.

Up another flight of stairs is a shooting range, marksmanship being a valued trait among a diaspora whose homeland has been occupied and liberated more times throughout history than a person has fingers and toes.

Taul, a retired architect, was two when her mother bundled her onto the boats. Tonu Orav, seated across from Taul, was even younger. Riina Klaas, to Tonu’s right, was born in Canada, but often heard her father-in-law speak of the boats. He left Estonia with two other vessels. His was the only one to survive the crossing to Sweden, a journey that claimed 7,000 lives.

Estonia lost a quarter of its population — about 250,000 people — during the war. When it was over, there was no going home. But there was Canada.

“I root for Canada in accepting the Syrian refugees,” Taul says. “Because, as Estonians, we have been there.

They arrived in Canada with nothing, built lives from nothing, and had Canadian-raised children who grew up and had children of their own — children who grew further and further away from the stories of the past and the church on Jarvis Street.

The Estonian and Latvian expatriate communities bought St. Andrew’s in 1951. They installed the refugee window in the 1980s. The church was sold this past fall, because of declining attendance.

But the window is still there, if you go looking for it. It faces south toward Lake Ontario. Toward the water, where so many refugee stories begin.

“It is a scene from our lives,” Nippak says. “We lived it.”